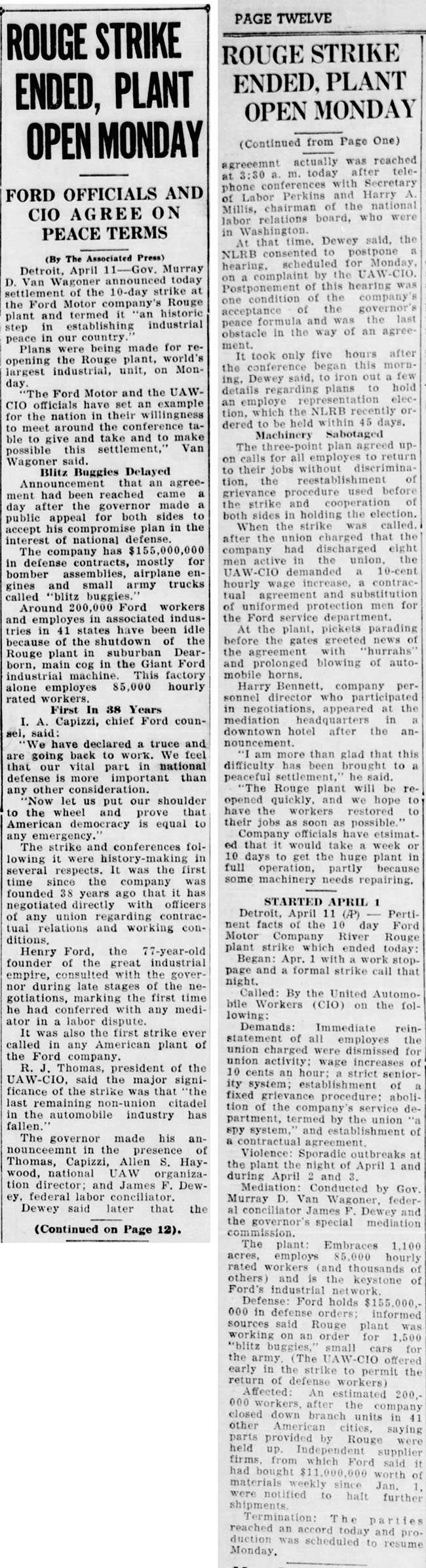

An April 12, 1941, article from the Escabana Daily Press out of California shows that it wasn’t always easy producing the Ford GPs. In this case striking works (and some reported sabotage of machinery) delayed manufacturing.

Long article from the same paper:

Reading this story, it surprised me that the union would call a strike during war time. The demand that eight fired workers be rehired, I see as justified, then the ten cent an hour wage increase, now thats really going to bat for your union workers. In today’s economy, the average worker has nothing to back him up. Ten cents an hour back then was a big deal, today, it’s nothing, yet many workers in America struggle to earn a living wage.

This was before Pearl Harbor, America was not yet at war. I would also be surprised if there were any labor strikes during the war effort.

I didn’t know the answer to the question of strikes during wartime. A quick review of newspapers indicate there were plenty of strikes. For example, a large coal mining strike (estimates between 400,000 – 500,000 workers) threatened to shut down the steel industry in the Spring of 1943. Workers complained that rising costs of living weren’t being offset by increases in pay, as the National War Labor Board (WLB) had frozen wages.

In May 1943 the Spicer Manufacturing company endured a 4000 worker strike that resulted in 1500 Willys-Overland employees being idled (and potentially forced to quit). During that same period, Timken was shut down for a 3-day strike and the Baltimore’s transit system was shut down due to a strike. Packard was also shut down during this period due to a strike. Akron Rubber workers struck as well, as they were unhappy with the WLB wage freezes. (these were all on one page of one newspaper)

By the summer of 1943 there was pressure on Congress to pass a law forbidding strikes by laborers in war industry companies (69% of the public polled indicated support). The house and senate passed a law, but FDR vetoed the legislation, which Congress overrode, creating the Smith-Connally Act: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Smith–Connally_Act.

But, the act didn’t make striking illegal; it just gave the gov power to take over companies with striking laborers. By November 1943, a majority of the public (69% in one poll) thought strikes in war industry companies should be made illegal, but I did not see any laws that arose as a result of that sentiment.

It would be easy to place all the blame on workers for the strikes, but they may well have had a grievance. War profiteering has been an American tradition since the American Revolution (here’s a bit on Civil War profiteers https://www.historynet.com/money-out-of-misery.htm), so these workers may have been angry that the companies were making profits, and the execs making more money, yet the workers were left to fend off inflation on their own.

My own grandfather, Rudolph Wurlitzer, saw his fortunes rise substantially during the Civil War as he was selling musical instruments to the Union. I have no evidence he was a profiteer, but he made good money none-the-less.

As demonstrated on a post somewhere herein, Willys-Overland’s finances turned around dramatically during WWII due to military contracts. So, did any of those profits flow to workers, workers who might have sacrificed wages to keep W-O going while W-O struggled financially prior to the war? Did execs profit due to WWII contracts? I don’t know the answers to these questions offhand. But, I expect with a little digging, we’d probably find that there was at least one strike at W-O during the war.

Thanks Dave, interesting information.

Thanks Dave, factual information I didn’t know. Just goes to show, as this talk about patriotism, what it really comes down to is the “almighty dollar”.

That’s why I find history fascinating. Usually when I think I roughly know the hazy history of some topic, research into it finds that there are critical aspects missing from my own understanding of the events. I’m definitely a research nerd.

Harry Bennett was a thug that ran the “service department”, which was actually a Gestapo-like department inside the company. He is famously known for carrying a gun and pointing it at people who disagreed with him, having a firing range in the plant where he and Henry Ford would “relax”, and for beating employees who were “disruptive” or engaged in union organizing. When Henry Ford turned the company over to Edsel Ford, Harry found himself out on the street.

Craig, I’ve never researched Ford history much. Those are some crazy details! I shall add a Ford biography to my reading list.

– Dave